Far from the spotlight, small-town Alberta suffers in upheaval sweeping energy sector

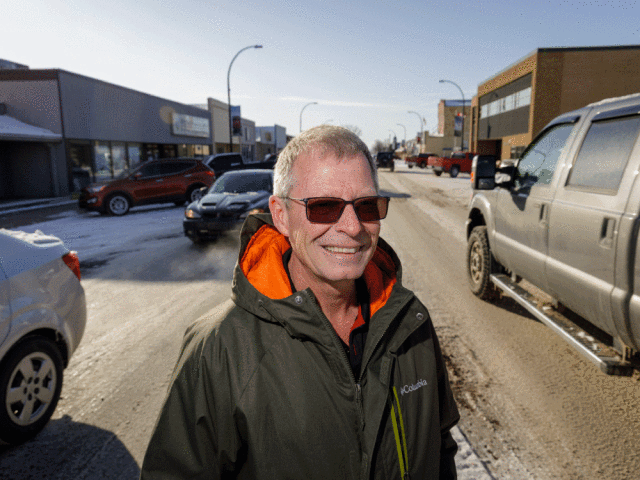

HANNA, ALTA. – Chris Warwick, Hanna’s Mayor and owner of the local Home Hardware franchise, was working at the store in November 2015 when he was blindsided by a call from a reporter informing him of the province’s climate-change plan.

The plan included a carbon tax that would make operating the town’s major employer, the Sheerness coal-fired power plant, more expensive in the short term and accelerate the phasing out of coal.

Residents in this east-central Alberta town of 2,500 feared they would lose as much as 10 per cent of their jobs if the plant, and the adjacent mine 30 minutes away, was forced to either shut down or be retrofitted to run emissions-free by 2030 as the previous NDP government’s climate-change plan demanded.

Since that call, Warwick said he’s been through the five stages of grief identified by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and, finally, acceptance. Others are still working their way through the process.

“There was a lot of anger there in the beginning,” Warwick said. “There are still people who are in that anger stage.”

Multiple residents and business owners used the word “disappointing” to describe their reaction to the coal-power phase-out, but also expressed extreme frustration about how their companies have been hurt.

“It’s a joke,” said Lane Rees, who owns Big Country Construction & Building Supplies Ltd. “That one hurt. It’s basically a whole complete economic shutdown.”

But Hanna’s problems were only beginning when the NDP announced its plan in 2015. The province soon entered a brutal depression, from which it has only had a nearly imperceptible economic recovery.

And then Westmoreland Coal Co., which runs the mine that feeds Sheerness with coal, entered bankruptcy protection in 2018. Housing prices collapsed to the point where detached three-bedroom homes — admittedly in need of repair — are being listed for as little as $20,000. People fled town.

“We just kept getting bad news after bad news after bad news,” Warwick said, adding that the three-year stretch between 2016 and 2018 was “devastating” for the town.

The challenges facing Hanna are daunting and encapsulate the economic pressures playing out across rural Alberta as the demand for lower-emissions energy has forced major structural changes in the energy and power markets, resulting in job losses and a sense of unease about how to prepare for the future while continuing to pay the bills.

Although the oilpatch’s woes affect Alberta’s large cities as well, they at least have more diversified economies to help reduce the pain and their populations are large enough that policymakers in Edmonton, though perhaps not Ottawa, can hear their anger.

In small towns such as Hanna, Warwick has found there are no easy solutions and few people are listening to their troubles.

For instance, in busier times, Big Country Construction employed as many as 13 people. Now, Rees said, there are just five employees including himself since very few people are spending any money on home construction projects.

“What’s happened lately is people are doing only what they have to in order to keep functioning,” he said. “No one is spending any money they absolutely don’t have to.”

But Hanna’s string of hard luck has shown signs of abating.